Fern syrup, stewed eel and native currant jam

This 1843 recipe collection may be Australia’s earliest cookbook

By Jacqueline Newling, University of Sydney and Alison Vincent, CQUniversity Australia

View of the town of Parramatta from May’s Hill, ca. 1840. Painting attributed to G. E. Peacock. State Library New South Wales

A chance find in a colonial newspaper from 1843 has us very excited: have we discovered evidence of Australia’s earliest cookbook?

Until now The English and Australian Cookery Book: Cookery for the Many, as well as the Upper Ten Thousand by Tasmanian Edward Abbott, published in London in 1864, have been credited with this honour.

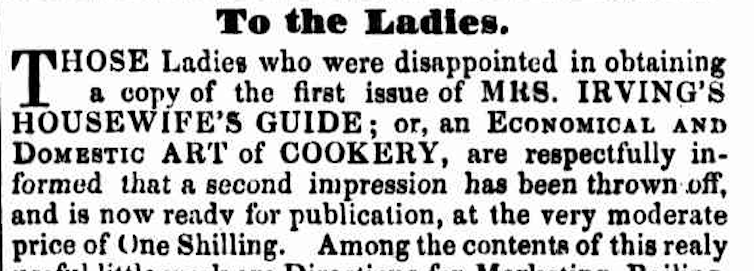

But when searching the National Library of Australia’s digital archive, our colleague Paul Van Reyk came across an advertisement in the December 30, 1843, Parramatta Chronicle and Cumberland General Advertiser for a cookbook none of us knew about: The Housewife’s Guide; or an Economical and Domestic Art of Cookery.

If this is indeed Australia’s earliest colonial cookbook, it would set the date back by 20 years.

The advertisement published December 1843. Trove

The advertisement published December 1843. Trove

A British recipe book

The Housewife’s Guide was published by Edmund Mason, who also published the Parramatta Chronicle.

The son of printer William Mason of Clerkenwell, London, Edmund arrived in Sydney in 1840 to work at the Sydney Morning Herald. He was employed there for two years before setting up his own printing business in Parramatta.

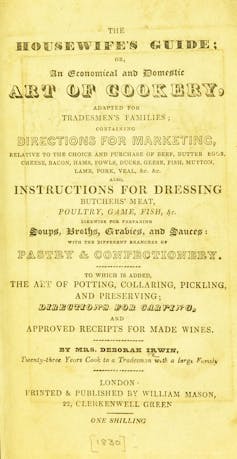

The title page of the original British version of the cook book. Wellcome Collection

The title page of the original British version of the cook book. Wellcome Collection

No author’s name is provided in the 1843 advertisement for The Housewife’s Guide, but a book with the identical title, written by Mrs Deborah Irwin, “23 years cook to a tradesman with a large family”, had been published in England by Mason’s father in 1830.

At the time, Australia’s cookery texts were generally imported from Britain, but Mason asserted this Housewife’s Guide was “the only work of the kind published in the colony”.

Perhaps through his father’s connections, Mason was printing Mrs Irwin’s text in downtown Parramatta.

A locally reprinted text does not, to our minds, qualify as an Australian cookbook. But reading the list of contents given in Mason’s advertisement, “native currant jam” leapt off the page.

It is unlikely English Mrs Irwin would have had native currants in her repertoire.

Australian ingredients

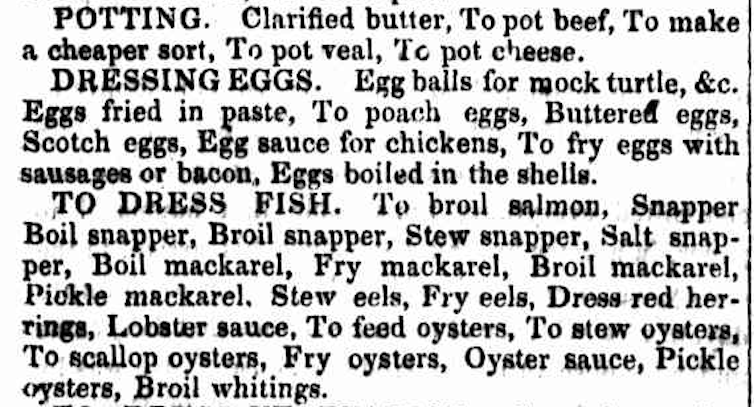

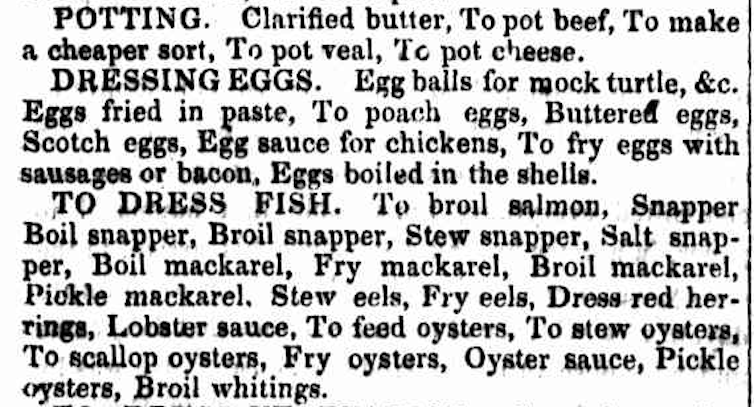

The 1830 edition of Mrs Irwin’s Housewife’s Guide has been digitised, allowing us to compare its contents more closely with the list provided in the Parramatta Chronicle. While there are clear similarities, with some sections possibly repeated verbatim, other significant differences convinced us this was a localised version of the original Irwin text.

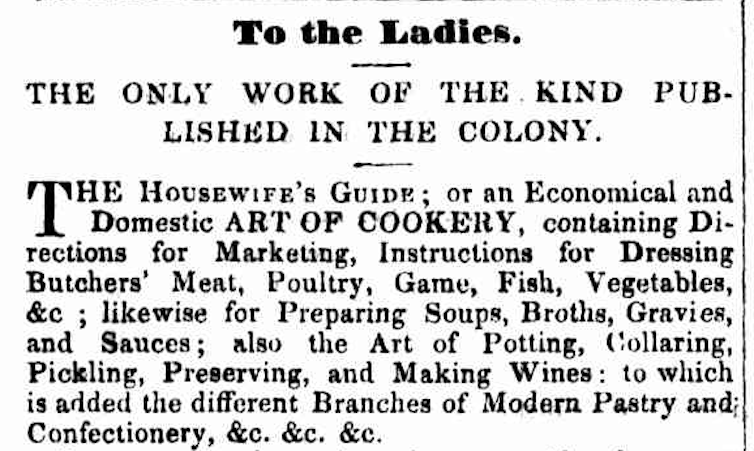

Fish species common in Britain – sole, carp, haddock, grayling, trout, perch, tench and others – do not appear in the local listing. Varieties such as salmon, mackerel and eels, which are found in Australian waters, have been retained, and snapper has been added.

The original advertisement listed the book’s recipes, including for fish available in Australia at the time. Trove

The original advertisement listed the book’s recipes, including for fish available in Australia at the time. Trove

Irwin’s Housewife’s Guide contains several recipes for game – hare, partridge, pheasant – none of which are listed in the Australian edition. Recipes for rabbits and pigeons, on the other hand, are found in both.

The Parramatta edition also has sections not included in Irwin’s book. A section on preserved meat provides instructions for salting and smoking mutton and ham.

A new section on syrups includes two which may have been incorporated for their local appeal: capillaire made from maiden hair fern – several species of which are native to Australia, and “Pine apply” (presumably pineapple) syrup. Highly exotic in Britain, pineapples were grown in colonial gardens and sold at produce markets.

Clearly this publication was not simply a reprint of Mrs Irwin’s text, but an upgraded, localised edition. It could also be the first formally published cookbook with recipes using native ingredients.

New mysteries

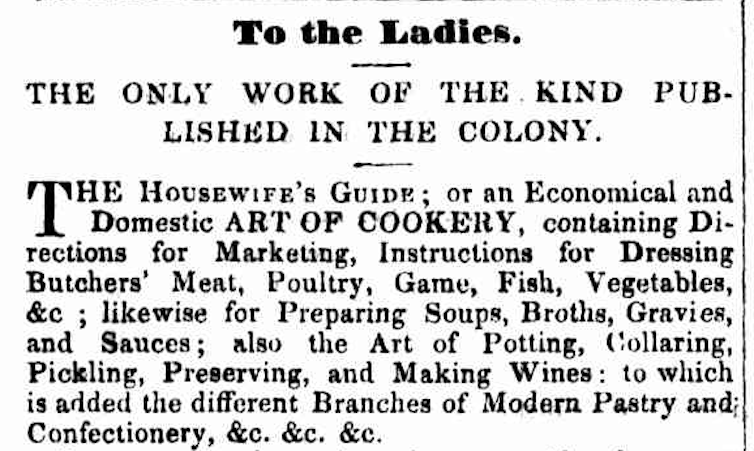

In July 1844 the Chronicle advised “a second impression has been thrown off and is ready for publication”.

This new round of advertising at last provided an author’s name, promoting the book as Mrs Irving’s Housewife’s Guide. The uncanny similarity between Irving and Irwin was impossible to ignore. Had Mason misspelled the name by accident or by intent? Was there indeed a Mrs Irving?

The cookbook was reprinted in 1844. Trove

We have not identified a Mrs Irving in the colony at this time, and we are yet to find a physical copy of this early colonial cookbook. It does not appear in library catalogues and has not been referenced in any bibliography of Australian cookbooks.

It is quite probable that no copies have survived the 175-plus years since they were published.

We can confidently claim however, that Mrs Irving’s Housewife’s Guide published by Edmund Mason in Parramatta is the first locally produced Australian cookbook. The majority of recipes may have been British by nature and origin, but departures from the British text are clearly aimed at localising the book for produce available in colonial New South Wales.

Mrs Irving’s Housewife’s Guide indicates there was an appetite for local culinary knowledge, and the use of native ingredients – rather than relying on British authority – 20 years before Edward Abbott’s The English and Australian Cookery Book.